The word “brigand” – brigante in Italian – is heard quite a bit with reference to Southern Italy, and I have noticed a certain confusion, particularly amongst English speakers, as to its significance. It’s an important term in understanding the Italian South and the history of Italy, so I thought I’d contribute my two cents to the question, “What is a brigand?” in an Italian context.

BRIGAND: IN THE DICTIONARY

Taking the dictionary definition, there’s no doubt, the term has strong negative connotations. Bandit, robber, outlaw, marauder and highwayman are common synonyms for brigand, which is often used to describe a member of a band that ambushes and robs people in forests and mountains.

Brigandry or brigandage – brigantaggio in Italian – is classically the form of the word that depicts the criminal activity carried out by brigands.

So why then, when in Southern Italy, do you hear the word brigante pronounced with a quasi-reverence?

Brigand and young Italian peasant girl in conversation at a fountain, watercolor on paper, by Carl Goebel

BRIGAND – BRIGANTE: HISTORIC USE

Words have a way of changing their meaning. In the Middle Ages, an Italian brigante was a type of foot soldier, an adventurous member of a mercenary unit. The term’s negative characteristics apparently came through the French, who used it during the Napoleonic period to disparage Italian revolts to their occupation. Thus, brigante referred not only to bandits in the pure sense of the word but also included those with social and political motivations.

Most notably, the word brigand has been employed to describe individuals and groups in Southern Italy, who combatted with troops of the new Kingdom of Italy during the Italian unification process, which was, in reality, an annexation by the House of Savoy. Not just isolated skirmishes, the revolt took on the form of a Southern Italian movement, particularly between 1861 and 1865, and is called the Grande Brigantaggio or the Great Brigandage.

Brigandage Museum in Rionero in Vulture, Basilicata – formerly the granary of a convent, the building was confiscated from the church in the Napoleonic period and was transformed into a jail, housing brigands amongst the inmates and eventually closing in 1967

WHAT IS A BRIGAND, HERO OR CRIMINAL?

History books, as we know, are written by the victors, so rest assured, most “evidence” of criminal activity in the archives will be detailed and well documented, at least from the official point of view. In Southern Italy, the vast majority of the accused never had an opportunity of defending themselves. This is not to say that every brigand was a saint; however, in the years following unification, there was a cause, and much of the activity could be characterized as falling somewhere between an uprising against an oppressive takeover and basic survival. Brigands included humble people and former soldiers. They were encouraged and aided by the Bourbons in exile as well as the Catholic Church.

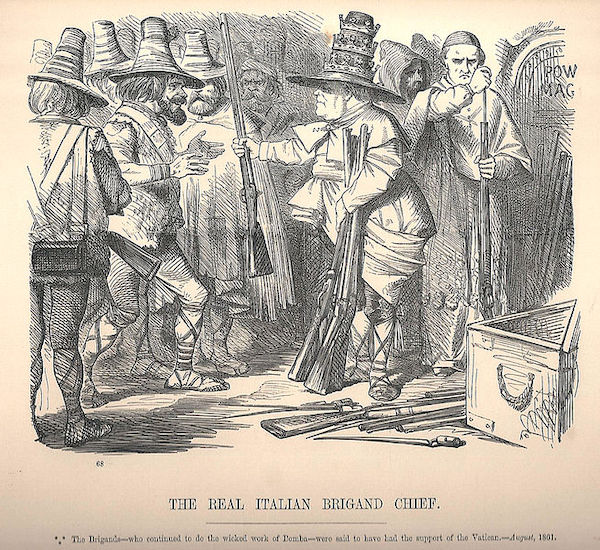

Satirical image of Pope Pius IX delivering weapons to the Southern Italian brigands on the cover of Punch Magazine, 1861

The opposition was massive. To give a brief idea of the force employed to squelch any resistance to the new monarchy, let’s look at Naples in 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II appointed Enrico Cialdini military commander of the city. In just the first couple of months under his control, his reports (as documented by Vittorio Messi in his book La sfida della fede) record staggering figures of the brutal Neapolitan repression: 8,968 shot dead, of which 86 were clergy, 10,604 injured, 7,112 prisoners, 918 houses burned to the ground, 6 towns completely burned, 2,905 families searched, 12 churches sacked, 13,629 deported and 1,428 towns under siege. Does that sound like a happy, Verdi-singing Italian unification to you?

Italy was criticized internationally for its ruthlessly cruel methods of suppressing the brigands. Such a drastic situation obviously sheds light on the mass emigration from Southern Italy that began in this period.

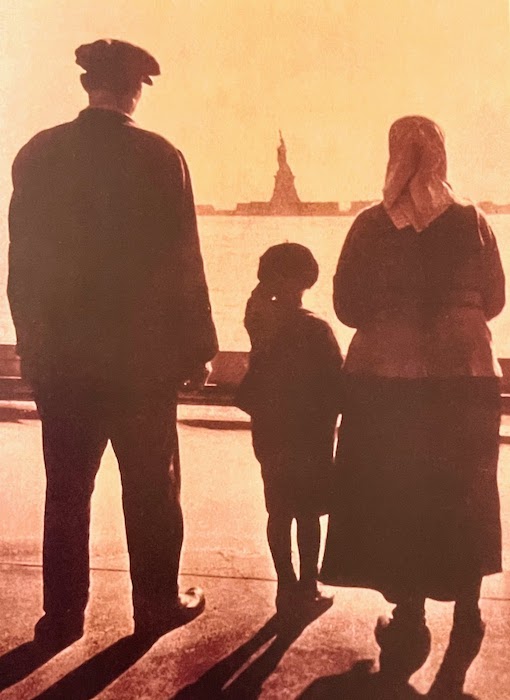

Emigrants on Ellis Island when, at the end of the 19th and start of the 20th century, the great Southern Italian immigration around the world began

And if it isn’t clear already, I would like to emphasize that the brigante and the mafioso are two different individuals entirely. Their association is a gross misconception. For southerners, the brigand is a folk hero, a Robin Hood figure in defense of his people. They were popular, locally and all the way up to an international level, with a distribution of their images on souvenir cards of photos taken at their capture, both dead and alive, as propaganda against them.

SOME FAMOUS BRIGANDS

As in the classic definition of a brigand, mountainous and wooded areas were their favorite haunts, remote locations not known to outsiders where they could more easily hide. Numerous stories and films portray some of the more famous brigands as attractive, heroic protagonists cutting brave figures in bucolic settings. For example, the town of Brindisi Montagna in Basilicata has an outdoor multimedia extravaganza every summer that tells the brigandage story featuring the region’s own Carmine Crocco with a cast of 300 and a host of animals in a large, natural amphitheater.

Crocco (1830-1905), nicknamed Donatello, worked his way up from humble birth to Generale dei Briganti or Generalissimo, a brigand general with an army of 2,000 men under his command. He was born in Rionero in Vulture, making him familiar with the isolated forests of northern Basilicata, an epicenter of the post-unification revolt. His intelligence and courage were admired internationally and although sentenced to death at his capture, he lived the last 29 years of his life in prison.

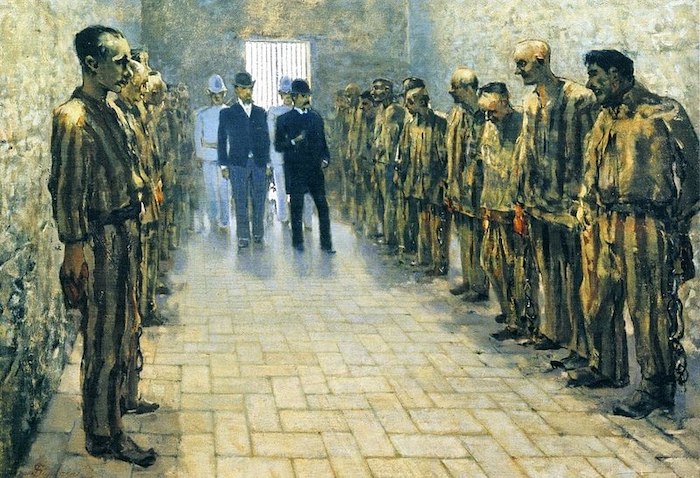

Bagno penale a Portoferraio (Bath at the Portoferraio penal colony on Elba) c. 1890 – Carmine Crocco is the first prisoner on the right – oil painting by Telemaco Signorini

Women were not immune to the fight, thus, the figure of the brigantessa, either the wife of a brigand, a woman with the courage and conviction of a brigand or a full-fledged weapon-carrying female brigand. Michelina Di Cesare (1841–1868) was all three. From a poor family and widowed early, she met a young man who would become head of a band in the area that is presently in the Province of Caserta (north of Naples near the border of Lazio and Molise), and became his close collaborator and active participant in the group.

Today, Di Cesare is best known for a posed photo in which she is dressed in traditional clothing with a double-barreled rifle and 2 pistols. Killed in action in 1868, she was disrobed and put on display in her town’s piazza as a warning for the local population, and her naked, mutilated body was photographed by the new government and circulated as a victorious memento.

WHAT IS A BRIGAND INTO THE 20th CENTURY?

The large bands of brigands were broken up by the late 1860s and with the military firmly in the hands of the Italian government, organized revolts of the Great Brigandage had come to an end by 1870. What remained was the “Piemontesizzazione” or the extension and application of economic, military and civic laws and policies of the Piedmont to the other territories in the new Italian state, which had a severely negative impact on the agriculture, industry and social existence of Southern Italians. These historic inequalities seeded and fostered a mistrust of the government that has continued through today.

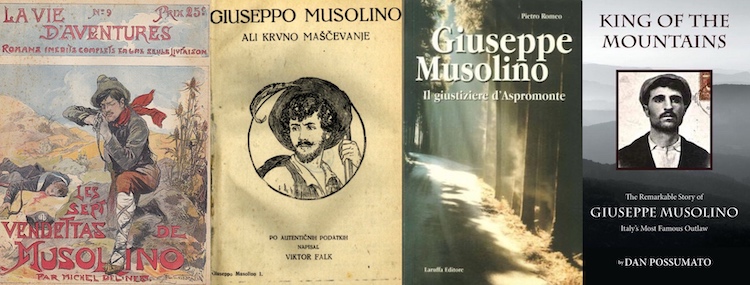

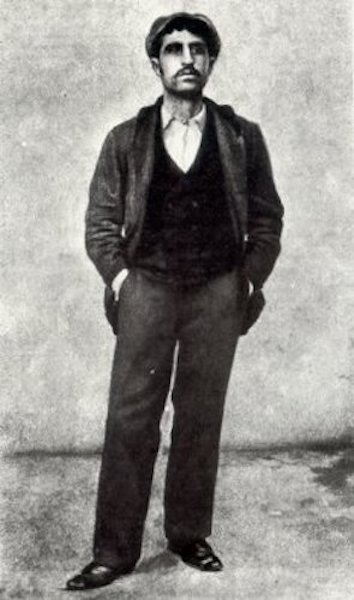

One of Calabria’s most famous brigands was born in the wake of the Great Brigandage. Giuseppe Musolino (1876-1956) would come to be called U ‘re i l’Asprumunti or the King of the Aspromonte and his name evokes pride in the hearts of Calabresi. His is a sad story, indeed, sentenced to 21 years in prison on false testimony of an attempted murder in his hometown of Santo Stefano in Aspromonte, located in the mountains above Reggio Calabria. Always maintaining his innocence, Musolino escapes from jail and evades arrest for 2 years as he hunts down his accusers, killing several of them and others in self-defense, assisted by people of the area, from peasant farmers to goat herders to the well-to-do who saw him as the symbol of the injustice dealt to Calabria.

At a certain point, Musolino decides to leave Calabria in order to ask the newly crowned Victor Emmanuel III for clemency, and as his bad luck would have it, he was arrested by chance in the Marche region when he tripped and fell as he ran from a pair of carabinieri who ironically hadn’t recognized him. He was given a life sentence and spent 44 years in prison and then his final 10 in a mental institution.

A few books and stories in different languages about Musolino: The Seven Vendettas of Musolino by Michel Delines (in French, 1908), Giuseppo Musolino by Ali Krvno Maščevanje (in Slovenian, 1909), Giuseppe Musolino, The Aspromonte’s Vigilante by Pietro Romeo (in Italian, 2003) and King of the Mountains by Dan Possumato (2013)

CALABRIA’S LAST BRIGAND

This past June on my Traditions and Food of Calabria Tour, we were strolling through the center of Longobucco, a town in the Sila Mountains, and happened upon Ottavio Forciniti (b. 1959), who is commonly referred to in the region as l’ultimo brigante or the last brigand. The chance encounter raised the “What is a brigand?” question amongst the group. Was he some sort of bandit?

Ottavio, the last brigand, was the youngest of 8, thus the name, and by the age of 5 was parentless. It was a hard life, growing up in a house without running water, always being told what to do and expected to work like his older siblings. He turned into a bit of a hothead, and as a volatile young man, got into a fight outside a bar, using a penknife with his thumb near the edge of the blade, jabbing his opponent a few times with the point. He ran. Better free than in prison. For 8 years.

He describes it as the life of an animal, hiding from his mistakes – in grottos during the day and under the stars when he moved at night, eating what he was able to find in the woods, what those who loved him left in concealed places and the occasional stolen loaf of bread. One day, he received a notice from Rome, saying he was free. At first, he thought it was a trick and remained in hiding, but in the end, the life of a hunted animal became too much for him and he gave up.

Today, Ottavio still spends most of his time in the open air, taking care of his free-range cattle the special Podolica breed of Southern Italy, the way his family has done for generations. His herd has never seen the inside of a stall. In hindsight, Ottavio would have done things differently. He never wanted to be a fugitive, preferring the brigante moniker. He’s had a lot of time to reflect and came across as a very gentle soul. He is free and embodies the brigand spirit.

The author in a brigand cloak in front of a quote by Carmine Crocco at the Museo del Brigantaggio in Rionero in Vulture, Basilicata: ““Without a doubt, I have done harm to society, but I did it in defense of my life, for which I would have set fire to the whole world.”

Interested in joining me on a tour of Calabria or Basilicata? Check out the itineraries of my Calabria Tours and Basilicata Tour, and get in touch!

Read all about the fascinating Calabrian region in my book Calabria: The Other Italy, described by Publisher’s Weekly as “an intoxicating blend of humor, joy, and reverence for this area in Italy’s deep south,” and explore Calabria’s northern neighbor in my book Basilicata: Authentic Italy, which has a chapter about brigands and is “recommended to readers who appreciate all things Italian” by the Library Journal.

Follow me on social media: Basilicata Facebook page, Calabria: The Other Italy’s Facebook page, Karen’s Instagram and Karen’s Twitter for beautiful pictures and information.

Sign up below to receive the next blog post directly to your email for free.

Comments 18

Great article! It was very exciting to actually meet the “The Last Brigand” in person on Karen’s outstanding Calabria Tour. Apparently, it is very rare to see the brigand in town. The tour was a trip of a lifetime! Thanks for a great experience!

Author

So glad you had such a wonderful time on my tour, with the bonus of running into the brigand!

Karen–After years of searching for a concise explanation of the brigantaggio phenomenon in southern Italy, this is the best I have read in English, which you have also put in its historical context.

I grew up with stories from my immigrant father, grandfather, about my grandfather’s experience as one of those who fought against Garibaldi in support of the Borboni as G. swept up through Italy with his army of a thousand.

The family story goes he was imprisoned by Garibaldi’s troops and was lucky to escape to continue his fight. A film made in 1961 by Mario Camerini called “I Italiani briganti,” [English translation: “The Seduction of the South”] with Vittorio Gassmann and Ernest Borgnine, supposedly was a fictionalized account of my great grandfather, Rocco Carbone. However, the name of this character in the film is Sante Carbone. My grandfather’s name. I have a copy of the film, but it is not subtitled, and my Italian is not quite good enough to understand the audio.

Unfortunately, my correspondence to Ernest went unanswered and an email to Lawrence Montaigne was answered by the actor, but he could not recall anything about the veracity of the film. Of course, most if not all of the actors are now dead, including Katy Jurado who was married to Borgnine for 10 years and divorced right after the film was released. The story and screenplay were written by Mario Monti and Luciano Vincenzoni who are both deceased as well.

Where do you think documentary evidence might be located? For that part of Calabria I am thinking that it might be Locri dell’Archivio di Stato di Reggio Calabria. At any rate, any guidance from your recent research would be appreciated.

Again, a great topic for you to address in your blog.

Fascinating – well written narrative about a group of people previously unknown to me. Nice job!

Author

So glad you enjoyed my post!

Excellent article – one difference between a brigand and a “murderous criminal” according to Eric Hobsbawm is that the ‘folk’ do not celebrate criminals in songs like they do brigands.

Jo Tedesco

Ps – I loved the book that I won from you many years ago

Author

Thank you, and great observation by Hobsbawm. He hits the nail on the head – thanks for sharing it.

My family, both sides(maternal and fraternal), came from Piane Crati, a small ‘commune’, up the hill from Cosenza in Calabria. They often spoke of the “Brigante Rosso,” who robbed and killed my maternal great grandfather (on her father’s side) while delivering wood from La Sila to the ‘comuni’ near Cosenza. (I think that’s where he was going.) Evidently it was a very dangerous job tgat few would consider. I didn’t read about Brigante Rosso so far in your blog. Any research on them?

Brenda

Author

I’m sorry your great grandfather was killed in such a terrible way. I haven’t ever heard of a group called “Brigante Rosso” and I also asked a Calabrian friend who is quite familiar with the brigandage history of the area. One explanation could be that Brigante is a last name in the Province of Cosenza. It comes from the verb brigare, not from the meaning of the word brigante as it has evolved. Perhaps the murderer had this last name with the nickname “Brigante Rosso.” It is also common for Italians to use articles before names which would make it sound like a group, as opposed to an individual, to an English speaker.

i found this on the web – but I have no idea what it means:) – seems to be the name of a wine!

https://www.vivino.com/US/en/brigante-etefe-rosso/w/3027416

Author

Yes, there’s a winery with the name Brigante in Cirò, Calabria, and they of course have red (rosso) wine.

Hi Cristina is the book in English? I think that there is a chapter in Norman Douglas’s book – https://www.fulltextarchive.com/book/Old-Calabria/5/

about brigands – it is interesting that we are getting information about italian brigands from a french/english perspective!

quote:

Calabrian brigandage, as a whole, has always worn a political character.

The men who gave the French so much trouble were political brigands, allies of Bourbonism. … The numbers of these savages were increased by shiploads of professional cut-throats sent over from Sicily by the English to help their Bourbon friends. Some of these actually wore the British uniform; one of the most ferocious was known as “L’Inglese”–the Englishman.”

Author

Yes, there’s a “Calabrian Brigandage” chapter in Douglas’ Old Calabria and also a “Brigandage” chapter in my Basilicata: The Other Italy book. Cristina is referring to a novel (in English) by a Calabrian-Canadian author, which you can read about on my blog: La Brigantessa by Rosanna Micelotta Battigelli.

Fascinating! I Briganti definitely have a Robin Hood vibe. The actress in Rosanna’s book trailer for La Brigantessa, Michaela Di Cesare, is actually a distant relative of Michelina Di Cesare. Have you seen it? She is beautiful. I will be seeing her in Torino in September and was actually thinking it would be cool to interview her. Ciao, Cristina

Author

Yes, I remember seeing the trailer and I thought, “What a coincidence, she has almost the same name as the famous brigantessa!”, which just goes to show, it’s a small world – she’s related!

Wonderful information! My father, we just found out through pure luck, was an orphan near Bruzano Zeffirio, Calabria, Italy. He was left on the doorstep of a couple that had two weeks earlier, lost twin girls at birth. Is it possible that I can find someone still alive that would recall a story like this from their parents or grand parents? My father came to America in 1915 but used a different surname then his adopted parents surname. We know this for certain because his step brother, five years his junior, lived in a nearby city in Ohio, the state they both settled in after arriving in this country. Our trip to Italy is next year. We hope to find documentation with more information and his actual surname before he came to the states. Again, thank you for this wonderful article.

I’m more interested on Brigand, as well as the Southern Italy vs. north.

Thank you.

Author

You can read more about brigandage, Southern Italian challenges and emigration in Basilicata: Authentic Italy.