Squillace, Calabria has been around for a long time. The history goes way back – think Ulysses. But for this post, I will focus on more recent epochs and highlight a time-honored artistic tradition with Squillace’s wonderful ceramics.

SQUILLACE, CALABRIA – HISTORY IN BRIEF

In early times, the city flourished near the seaside under the Greeks, the Brutti, the Romans and Byzantines, and to trace these ancient civilizations, you can visit the excellent Scolacium Archeological Park, today in Roccelletta di Borgia. As the story goes, Saracen incursions brought about the decline of the prime coastal location on the gulf of Squillace along the Ionian Sea. The people fled inland to hilltop positions, such as Squillace, at an altitude of 360 meters (over 1,000 feet) and only 15 kilometers from the sea.

Squillace’s highland continued to be a target for the Saracens, and the town was dominated by the Arabs in the 10th and 11th centuries, eventually beaten back in 1044 by the Normans, who built a castle on the site of the Byzantine-Arab fortifications. Numerous rulers, battles and earthquakes, particularly that of 1783, have all taken their toll on the imposing structure as well as the town itself, but the majestic castle ruins at the city summit are an impressive reminder of Squillace’s significant past.

Located in the Province of Catanzaro, Squillace’s territory extends from the hill down to the sea, and today’s visitor has lovely views over the countryside from its strategic position.

SQUILLACE CERAMICS

Even if you happen to stumble upon Squillace without knowing about its ceramic tradition, you can’t help but notice the numerous shops with colorful terracotta pieces displayed in the windows as you wander through the old town. In fact, Squillace’s characteristic ceramics have led to the granting of “DOC” status to local artists, a mark of quality and authenticity, as well as protection. Incidentally, the DOC regulations give the town’s potters leeway to source clay with the same properties from other areas, as Squillace doesn’t have an industrial-level operation to purify local clay for use in fine ceramics.

The history of terracotta production in the area dates back to at least the Greek period, evidenced by tableware, pots and larger amphoras found in archeological sites. Productivity continued throughout successive dominions. Cassiodorus, Roman statesman and the most illustrious citizen of Squillace’s predecessor, Scolacium, considered ceramic arts important to society and promoted their interests within the Ostrogoth administration, for which he served as minister in the 6th century.

The activity flourished under the Byzantines and Normans, and later on, in the 16th century, Gabriele Barrio gave details of Squillace’s ceramics in the first history of Calabria, written in Latin in 1571. At that time, he documented 31 ceramicists in Squillace, of which 10 produced faience, 21 were masters of the pignata (terracotta vessels usually used to cook beans over an open fire), and the city had at least 15 kilns. Interestingly, a few decades before the earthquake of 1783, the area of the castle that had been dedicated to the militia was transformed into a workspace for artisans making terracotta pots, an enterprise that literally smashed to pieces with the earth’s devastating movement.

The following image of a large, ornate platter is a splendid example of Squillace’s historic ceramics. The piece, dated 1684, was created using the technique the town is still known for today. The beautiful presentation dish has unfortunately been lost…

SQUILLACE CERAMICS – TECHNIQUE

The type of clay found in the Squillace area is particularly suited for the execution of everyday crockery as well as the graffito technique for which artisans of the town became to be known. This practice of “scratching” out a design stems from the Byzantine period. First, the clay is shaped by hand on a potter’s wheel and allowed to dry naturally for a few days. Then, an ingobbio layer (engobe in American English, slip in British) of thin white clay is applied over the surface. After drying a couple hours, the engobe is scratched away with the sgraffito or incising technique, revealing the contrasting color underneath.

Historic examples of Squillace ceramics can be found in museums and private collections around the world, including this lovely container dating from about 1650 on display at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum. The honey-yellow-glazed wavy foliage stands out beautifully against the red earthenware surface.

And here is a broken piece of antique pottery with identical coloring and similar undulating motif that Beatrice Russomanno showed me in her family’s shop “Il Tornio” in Squillace’s old town.

VISITING SQUILLACE CERAMIC SHOPS

Squillace has numerous artisans carrying on its ceramic tradition. Wandering through the streets of the old town and ambling into the shops, you can find ceramicists at work with tool in hand, employing the sgraffito technique, such as Graziella in the studio of “Ideart” . . .

. . . with a few tools of the trade . . .

. . . scratching designs into clay pieces which reveal the characteristic reddish-brown and white finish after firing in the kiln, both small . . .

. . . and large.

“Ideart” may have a contemporary name, but Graziella’s husband, Antonio Commodaro, comes from a family of ceramicists dating back at least to the 18th century. His forebear Tonino Commodaro is registered as a master potter in a Bourbon ledger of 1756! Squillace also has an old workshop that dates back to the 1600s, which closed its doors in the 1970s as it produced everyday items that were supplanted by plastics and items of modern manufacture.

Nearby, “Il Tornio” has a large showroom of work produced by husband and wife team of Beatrice and Claudio Panaia. They make reproduction terracotta pieces using the engobe and sgraffito technique of the characteristic reddish earth tones contrasted with white, as well as yellow-glazed pieces and those in the style of the ancient Greek black and red figure pottery.

In the following photo, Beatrice shows off her stunning work, a smaller, two-toned reproduction of the 17th-century platter pictured above. Squillace’s typical engobe-sgraffito technique highlights intricate floral designs, images of animals and other decorative elements.

“Il Tornio” and others also produce smaller gift objects, made-to-order pieces and attractive tableware in painted majolica, such as a set of dishes decorated with this uccellino della fortuna or little bird of fortune, intended to bring good luck. This tiny feathered creature perched on a bed of thick leaves hails from the early 18th century, but his good karma carries through to today!

Do you like what you see? Visit Squillace with me on my Traditions and Food of Calabria Tour!

Check out other Calabresi carrying forth artistic traditions in Calabria: The Ceramics of Seminara, Textile Artist Domenico Caruso, A Dream in Terracotta, An Artist in Amantea, and Eco-Printing and a Day in the Caulonia Countryside.

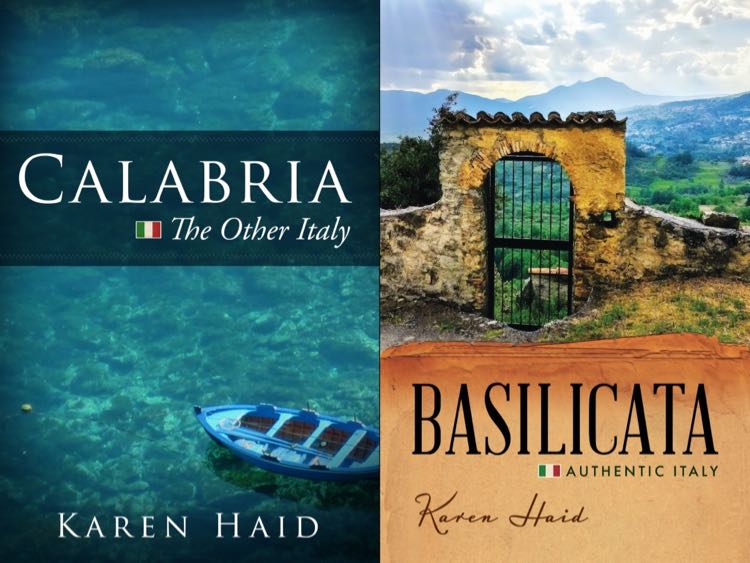

Read more about the fascinating Calabrian region in my book Calabria: The Other Italy, described by Publisher’s Weekly as “an intoxicating blend of humor, joy, and reverence for this area in Italy’s deep south,” and explore Calabria’s northern neighbor in my book Basilicata: Authentic Italy, “recommended to readers who appreciate all things Italian” by the Library Journal.

Follow me on social media: Basilicata Facebook page, Calabria: The Other Italy’s Facebook page, Karen’s Instagram and Karen’s Twitter for beautiful pictures and information.

Sign up below to receive the next blog post directly to your email for free.

Comments 8

Beatrice is very talented! I have always loved ceramics. I would definitely spend too much $ if I visited Squillace! Ciao, Cristina

Author

That is always the risk! But window shopping is also nice.

Amo calabria per sempre.

Author

Grande!

Wow. I don’t know why I’m always amazed at the artistry and intricacy of work done by peoples in the past. It’s nice that this particular craft knowledge has not been lost through the ages.

Author

I agree. Somehow we are led to believe that our society has evolved and that what we create today is better than that of yesteryear. One glance at past artistic traditions and accomplishment puts perspective on it all.

My grandfather, Domenico Commodaro, emigrated from Squillace in 1919, he was the youngest son, Vincenzo was his nephew.

Author

Interesting, was your grandfather part of the Commodaro family who worked in ceramics?