Calabrians have an infinite number of sayings and proverbs, and with all the different languages, dialects and neighborhood variations, I cannot begin to scratch the surface of the verbal expressiveness. So here are just a few proverbi calabresi to whet your linguistic whistle. Animals are the common thread.

THE DONKEY

The donkey, noble beast of burden, transportation for and companion of the humble calabrese, is featured in numerous proverbi calabresi. There’s even a local breed, the asino calabrese, called u ciucciu in northern Calabria and u sceccu in southern parts. As with all companions near and dear, they are sometimes loved and admired, and at other times, maligned.

’U piaciri du’ sceccu esti ’a ramigna.

Il piacere dell’asino è la gramigna.

The donkey’s pleasure is scutch grass.

Not only does the donkey do man a favor by controlling a wild grass that is often seen as invasive, the animal actually enjoys it!

U sceccu chi mangia ’a ficara si leva ’u vizziu sulu quandu mori.

L’asino che mangia l’albero di fico perde il vizio soltanto quando muore.

The donkey who eats fig trees, loses the bad habit only when he dies.

This saying is used sarcastically as donkeys don’t browse on the leaves of fig trees. It is said to someone who states or does the same things over and over.

THE PIG

Pork is king for the cucina calabrese (Calabrian cuisine) – think of the wonderful cold cuts, sausages and salami, and then there’s the frittole from the Province of Reggio Calabria. Thus, it may not come as a surprise that Calabria also has its own breed, the suino nero di Calabria or nero calabrese, the Calabrian black pig.

Non nci dari confetti e’ porci.

Non devi dare confetti ai maiali.

You mustn’t give pigs sugared almonds.

Confetti are almonds with a hard, candied shell, a symbol of fortune and prosperity, traditionally given out at weddings. The expression counsels that it’s useless to give nice gifts to those who can’t appreciate them.

U porcu a notti si ’sonna a ghianda.

Un maiale la notte sogna la ghianda.

A pig always dreams of acorns.

This proverb observes those who fixate on the same pleasurable things.

THE SHEEP

Sheep and their fluffy wool are not to be left out of the catalogue of proverbi calabresi. In addition to the wonderful cheese made from their milk, the region has also produced beautiful woolen textiles. And thinking of that lovely fleece . . .

Quandu’ u’ celu è pecurinu l’acqua è certa pù matinu.

Cielo a pecorino pioggia certa per il mattino.

When there are sheep in the sky, it is sure to rain in the morning.

Of course, this proverb refers to puffy, cumulus rainclouds.

Mara ’a pecura c’ ’avi a ddari ’a lana.

Povera pecora che deve dare la lana.

A poor sheep who has to give wool.

This proverbio calabrese refers to someone in debt, who, sooner or later, must pay it back.

THE WOLF

“Il Lupo della Sila” – Wolf of the Sila by Mimmo Rotella, Museo all’aperto Bilotti, Open-air museum in Cosenza

Wolves are present in all the mountainous areas of Calabria, and il lupo is the symbol of the Sila National Park. Historically, they have been seen as the enemy, due to their nature of attacking sheep, and back in the day, wolf mementos and amulets were used to combat the evil eye, to bring luck, and in various folkloristic rituals.

U lupo cangia u pilu ma non u viziu.

Il lupo perde il pelo ma non il vizio.

The wolf changes his coat but not his disposition.

I think we’re all familiar with the wolf and his bad habits, as . . .

Tuttu u mundu è paisi.

Tutto il mondo è paese.

All the world’s the same.

Other blogposts with proverbi calabresi: Wisdom on a Sugar Packet, A Dream in Terracotta, Le Frittole, Festival of the Madonna, Lent in Italy.

If you’re wondering about the difference between calabrese and calabresi, see this article: Calabres, Calabrese, Calabresi?

Visit Calabria on one of my small-group tours and hear some proverbi calabresi first hand!

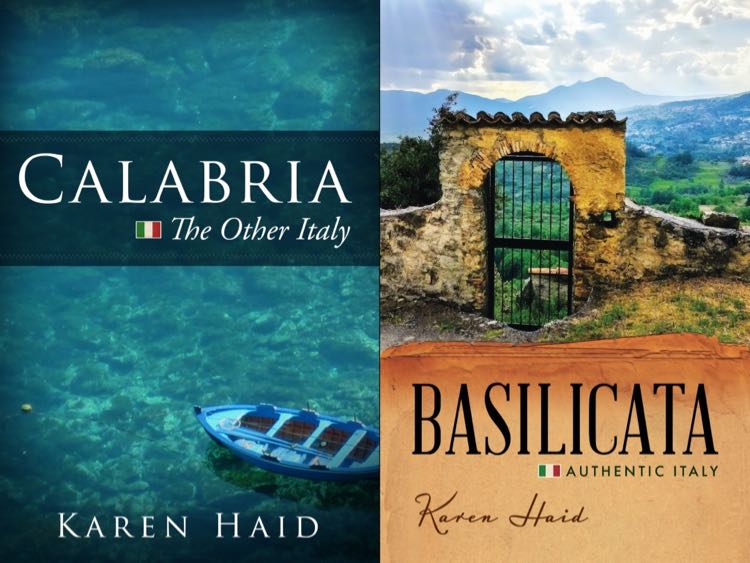

Read more the fascinating Calabrian region in my book Calabria: The Other Italy, described by Publisher’s Weekly as “an intoxicating blend of humor, joy, and reverence for this area in Italy’s deep south,” and explore Calabria’s northern neighbor in my book Basilicata: Authentic Italy, “recommended to readers who appreciate all things Italian” by the Library Journal.

Follow me on social media: Basilicata Facebook page, Calabria: The Other Italy’s Facebook page, Karen’s Instagram and Karen’s Twitter for beautiful pictures and information.

Sign up below to receive the next blog post directly to your email for free.

Comments 2

Another fine post, as always. Thanks for providing the standard Italian beneath the Calabrian dialect. If I may be so bold, here is a little poem about a story my grandfather used to tell. It has a sceccu in it, but I call it a burro, something most Americans could relate to.

Ancestral Altar Boy

In memory of Pasquale Altomonte, 1895-1987

1908, Agnana Calabro.

Past the gauntlet of frosty cactus paddles,

his load of firewood shifting in the saddle,

a boy with kinky hair tugs the burro

up the steep lane to the little church

walking backwards, eyeing the cemetery

straining its walls like a distant feudal city

just waking up to dawn’s feeble torch,

below that the river, and beyond the hills

ascending to Gerace’s high ruin.

Vendetta, earthquake, drought, the wages of sin.

He looks to the priest whose coins help him fill

his belly. But the priest has had to wait

too long today beside the cold stove.

Scolded, the boy kindles the fire, then serves

at mass in his dirty surplice. The priest forgets

to pay. No, no one owes him a damned thing,

foundling who leads the burro down the lane

he will never take up to the church again,

and feels in his gut a cactus needle’s sting.

In an otherwise very devout family, my grandfather was alone in refusing to go to church except for weddings, funerals, and christenings. And in our family lore, this little incident was his reason.

Author

Thank you for sharing your poignant poem, what a hard life you’ve so beautifully described. It’s no wonder your grandfather could not bring himself to attend church regularly, his young existence much like that of the burro, left wanting just a minimum of appreciation.