Before visiting the Museo San Paolo housed in Reggio Calabria’s Palazzo della Cultura, I was under the impression that it was just the usual collection of a couple pieces of silver, a few religious paintings and an old frock. How many times have I paid the Euro and gone through a side door past a heavy velour curtain to view a handful of dusty antiques with dubious value? Well, this wasn’t one of those occasions.

PICCOLO MUSEO SAN PAOLO

First of all, the museum is free and in a newly renovated building. Before the opening of the Palazzo della Cultura, the collection was apparently in tighter quarters behind the nearby Santuario di San Paolo, also known as San Paolo di Rotonda. (And by the way, I recommend a visit to this nearby church, which might just make you gasp at the glittering mosaics in its richly adorned interior.)

The St. Paul Museum’s official name is Piccolo Museo San Paolo. I haven’t been able to determine if the piccolo is a misplaced modesty or has some other significance, but I didn’t see anything small about it.

Museo San Paolo in the Palazzo della Cultura

MONSIGNOR FRANCESCO GANGEMI, THE FOUNDER

The driving force behind the museum didn’t spend his life thinking small, either. Born in Reggio Calabria in 1906, Mgr. Francesco Gangemi served at the church of San Paolo di Rotonda for over sixty years, taught in a theological seminary and in public schools, wrote, preached and even composed a couple of operas, including the libretti.

These activities all sound like what one would expect of a priest, except perhaps for the bit about his musical compositions, and you might think that, all told, it would have made for a very full life. However, there’s more to the story. Mgr. Gangemi was also an art lover, indefatigable collector and founder of this piccolo museo, an eclectic mix of icons, paintings, sculpture, silver, books and archeological artifacts.

THE ICONS

Russian icons of the 20th century

For many, the jewel of the museum’s crown would be the icons. But what inspired a Roman Catholic priest to collect these symbols of the Orthodox church? The answer could lie solely in their beauty, but perhaps the interest also speaks to Calabria’s historical ties to Eastern Christianity. From the 6th to the 11th centuries, most of Calabria was Byzantine. In fact, many churches in the region have Byzantine architectural roots, and the Greek rite survived in some areas up until 1480, when it was abolished in favor of the Latin service. To this day, there are several communities in the Province of Reggio Calabria where the local dialect is a form of ancient Greek.

St. George icon, Greece

The museum has almost two hundred icons that come from Eastern Europe and the Balkans, and in particular, the countries of Russia, Rumania, Bulgaria, as well as Greece. A number of the paintings have ornate silver coverings. An exceptional piece in the collection is the 18th-century icon representing the Madonna and St. Gerasimus that is most likely of Calabrian origin.

Madonna and St. Gerasimus, 18th cent., probably from Calabria

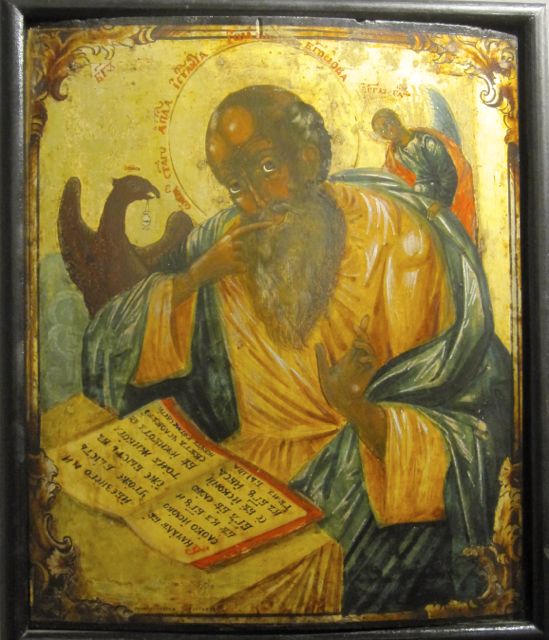

St. John the Apostle “In Silence,” 18th-19th cent., Russia

IVORY SCULPTURE

Ivory Crucifix, 16th-17th century

The museum’s numerous ivory pieces also caught my eye, but perhaps more than the large crucifix mounted prominently on the wall, the display case with an assortment of smaller pieces piqued my curiosity. Many were secular and of Asian origin. Interestingly, a beautiful French gothic Madonna with Child from the 13th-14th century, a few statuettes from the Italian Renaissance and a miscellany of crucifixes were displayed together with a 19th-century geisha.

Madonna with Child (15th cent.), Geisha (19th cent.)

THE SAINTS IN REGGIO

Amongst the many paintings, San Michele che uccide il drago (St. Michael Killing the Dragon), a large image on a wooden panel stands out for both the beauty of the work and its history. Dating from 1470, this painting of Saint Michael the Archangel was for many years attributed to Antonella da Messina. For this reason, the piece was analyzed in great detail. Even though it was determined not to be of the hand of the renowned artist, which is of no great surprise, the physical state of the image was studied more than perhaps it otherwise would have been.

St. Michael Killing the Dragon, 1470, 198 x 105 cm, Courtesy of Museo San Paolo

At first glance, coming across this painting in a museum, you might just think that due to its more than 500-year existence, a little paint had chipped off here and there. However, the damage to the saint’s face has actually been ascribed to historical vandalism. In the 16th century, Reggio suffered terribly from attacks by Ottoman Turks and Barbary pirates. These invaders defaced, literally, religious paintings and chopped the heads off of and otherwise damaged sculptures. Thus, Saint Michael the Archangel suffered from this collateral damage.

Saint Michael the Archangel, detail

Today, these events might seem like ancient history. However, their memory is still very much alive in a common saying in the local dialect:

Simu cumbinati comu i santi reggini. (in Reggio dialect)

Siamo ridotti come i santi reggini. (in Italian)

We’ve been reduced to such a state, like the saints in Reggio. (in English)

OTHER PAINTINGS AT THE MUSEO SAN PAOLO

In addition to Saint Michael the Archangel, the Museo San Paolo has over 140 paintings in its collection. The works date from the 15th to the 20th centuries and comprise of canvases and panel paintings of the Neapolitan and Flemish schools, as well as those by other southern, including Calabrian, artists.

A few paintings struck me in particular. The 16th-century work on board entitled Santi domenicani e anime purganti (Domenican Saints and Purged Soles) made me wonder just what everyone in the painting was looking at, thus concluding that it must have been a cutout from a larger painting.

Domenican Saints and Purged Soles, unknown 16th-century southern Italian painter, mixed media on board

The vibrant colors and forms of the figures in Cristo deriso (Mocked Christ) caused me to take a closer look. This 17th-century work from southern Italy was an oil on slate.

Mocked Christ, 17th-century Southern School, oil on slate

The elaborately carved wooden frame of the Adorazione dei Magi (Adoration of the Magi) was what turned my head toward the tempera on board of the 15th-century Flemish school. Rare to see what may have been an original frame on such an old painting, with the frame being perhaps more beautiful than what it held.

Adoration of the Magi, 15th-century Flemish School, tempera on board

SILVER, BOOKS, ETC.

For those interested in silver, this Reggio museum offers a collection of chalices, monstrances and incense burners by Sicilian, Calabrian and Neapolitan master smiths from the 15th to 20th centuries. And there are even ornate old frocks in very nice condition.

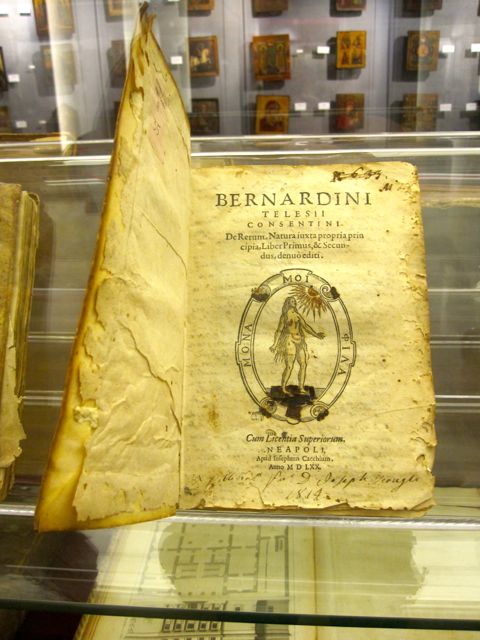

The foundation’s library is also worthy of mention. Very large, the Museo San Paolo collection includes parchments that run the gamut from commercial contracts to pontific bulls and decrees, dating from 1200 through the high medieval period. A highlight of the many volumes from the 15th-century is an incunabulum De Bello Judaico (Jewish War) by Giuseppe Flavio, a 1st-century Roman-Jewish scholar known as Josephus in English. Books run up through the modern period and include volumes of local interest, for example the 16th-century philosopher and naturalist Bernardino Telesio from Cosenza.

Bernardino Telesio, De rerum natura iuxta propria principia

I was lucky to have stumbled through the museum’s heavy door located on the ground floor of the Palazzo della Cultura and to have met Fabio, a friendly, informative volunteer, eager to share his knowledge of the collection. Maybe he’ll be there on your visit – this is one of those museums, piccolo as it may be, that you’re not going to want to miss!

Where is the Museo San Paolo and what is the Palazzo della Cultura? Read all about it on my blog post The Palazzo della Cultura in Reggio Calabria.

Interested in more of what there is to see and do in Reggio Calabria, the beautiful city right at the point of the toe in the Italian boot? Here’s a link to my blogpost Visit Reggio Calabria, and for more about Reggio and the entire region of Calabria check out Calabria: The Other Italy, my non-fiction book about daily life, history, culture, art, food and society in this fascinating southern Italian region. Available in paperback and electronic versions.

Interested in more of what there is to see and do in Reggio Calabria, the beautiful city right at the point of the toe in the Italian boot? Here’s a link to my blogpost Visit Reggio Calabria, and for more about Reggio and the entire region of Calabria check out Calabria: The Other Italy, my non-fiction book about daily life, history, culture, art, food and society in this fascinating southern Italian region. Available in paperback and electronic versions.

“Like” Calabria: The Other Italy’s Facebook page and follow me on Karen’s Instagram and Karen’s Twitter for more beautiful pictures and information.

Sign up below to receive the next blog post directly to your email for free.

Comments 6

It DOES appear to be a very beautiful museum!

The sad history of some of the vandalism, only shows that history DOES repeat itself …… now happening in the current terrible destruction of so many religious icons, statutes, etc., all in the NAME of religion!!!

Author

So much for learning from our mistakes…

Great post. All very interesting and worthy of another visit. Looking forward to it myself!

Author

Yes, the Palazzo della Cultura is a wonderful addition to Reggio’s cultural offerings.

Just wonderful, I love it!

Looking forward to heading down that way & exploring it all in summer.

Thank you.

Author

Thanks. I’m sure I don’t need to mention this, but when in Reggio don’t forget to set aside a nice chunk of time for the Riace Bronzes and the Archeological Museum. Enjoy!