Personal integrity, cultural strength and a collective resilience—these are just a few of the characteristics that helped Matera survive its difficult past and come out the other side to be distinguished as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a European Capital of Culture. This fascinating city in the southern region of Basilicata, wedged between Calabria, Campania and Puglia, is known the world over for its “Sassi,” ancient “stone” neighborhoods carved out of the rocky landscape, made famous as the set for such films as Il vangelo secondo Matteo (The Gospel According to St. Matthew, 1964) by Pier Paolo Pasolini, Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ (2003), and the latest James Bond movie No Time to Die (2021).

MATERA: UPS AND DOWNS

Directors are captivated by Matera’s unique landscape and seek out the Città dei Sassi for its primitive beauty and anthropological interest. However, the spotlight was far from favorable back in 1945 when Matera leaped to the international stage with Carlo Levi’s scathing condemnation of the poverty-stricken area in his memoir Cristo si è fermato ad Eboli (Christ Stopped at Eboli). The Sassi immediately became a “vergogna nazionale.” But amazingly, in just a little over 70 years, Matera has gone from being a “national disgrace” to becoming an international tourist destination, designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and honored by the European Union for its cultural value.

The transformation of Matera is not a simple tale of neighborhood rehabilitation. Its success is not due to hipsters opening trendy restaurants. Rather, the credit belongs to a people, their culture and a more than 2,000-year thread of life in the historic Sassi district. Matera’s story is one of adaptation, innovation and tradition.

MATERA HISTORY

Inhabitation of the area dates back to the Paleolithic Era. Remains of entrenched Neolithic villages have been discovered on the eastern cliff of the Gravina di Matera, the canyon along which the city is situated. With the development of metal tools, dwellings were dug out of the gorge’s porous limestone, often generically referred to as tufa, and a community sprouted on the opposite bank, where the Sassi sit today. The blocks excavated from the caves were subsequently utilized for exterior construction.

In the early medieval period, monastic communities arrived from the east. Contributing to both the spiritual life and the area’s urbanization, these religious figures created beautifully frescoed grotto-churches. Several of these chiese rupestri, of which over 150 have been uncovered, still functioned as places of worship into the 20th century. Others were used as living quarters, stalls, storage facilities or had been abandoned.

The Sassi districts sit on the edge of a ravine and appear as a valley when viewed from the upper level of Matera, known as the Civita, the city’s oldest institutional settlement. The Civita was once surrounded by a protective wall, the arched gateways of which can still be seen amongst the more conventional architecture on this strip of higher ground that extends between and divides the Barisano and Caveoso Sassi. In the 13th century this central location was chosen for construction of a magnificent cathedral whose tower still dominates the city skyline. The Duomo di Matera is one of many exquisite edifices constructed in the Civita and Piano districts. Visitors who only expect to see the Biblical starkness of the Sasso Caveoso neighborhood crowned by its evocative rock church dedicated to Maria de Idris are often surprised by the resplendent European architecture spanning from Romanesque to the Baroque.

SASSI DI MATERA – ECODESIGN

The Sassi, themselves, are no less extraordinary. In fact, Matera’s Sassi and Park of Rupestrian Churches were honored by UNESCO in 1993 as “the most outstanding, intact example of a troglodyte settlement in the Mediterranean region, perfectly adapted to its terrain and ecosystem.” The city’s historic system of water collection with its pioneering conservancy of this precious natural resource was revolutionary for its time. In addition to excavating living quarters, the Materani also dug a sophisticated network of tunnels and cisterns that branched like tree roots beneath the entire community. Many homes in the Sassi had their own cistern, others shared a neighborhood reservoir. They collected rainwater and funneled water from a nearby spring, as well as channeled watercourses for drainage and sewage. The largest cistern within the system, the Palombaro Lungo, was built in the 19th century and supplied water for the Piano, the Baroque section of the old town.

The architectural layout of the Sassi fostered social interaction as homes faced onto small squares with shared cisterns and ovens. Numerous houses were designed with a lower-level cave serving as a warehouse and residential quarters fashioned out of the excavated rock on the floors above. Living conditions began to decline from the 17th century onward, however. As the population increased, more and more people were forced to live in a space not able to satisfactorily accommodate them. Many were compelled to take up residence in grotto churches, animal shelters, storage caves and even cisterns.

EVACUATION AND REEVALUATION OF THE SASSI

By the time writer and social activist Carlo Levi compared the Sassi to “a schoolboy’s idea of Dante’s Inferno,” and spoke of children begging in the streets, not for candy, but “with sorrowful insistence, for quinine,” the crisis had long passed its breaking point.

The infant mortality rate was four times higher than the national average. Politicians could no longer ignore the city’s abominable sanitation and in 1952 responded to the humanitarian crisis with a law mandating the evacuation of the Sassi residents, over 15,000 people, half the population of Matera. Over the following years, new, modern quarters were built and the people moved out of the Sassi neighborhoods. The move must have been disconcerting for the elderly; however, the new accommodations were welcomed by large families who suffered in the humid, overcrowded cave dwellings that they shared with their animals, if they were lucky enough to possess a donkey and a few chickens.

The evacuation took place over a twenty-year period. During that time, the Sassi were kept alive by filmmakers and the residents’ collective memories. Almost fifty films have capitalized on Matera’s unique beauty. The Sassi were destined to be more than a backdrop, however, and determined Materani worked hard to show themselves and the world that the spontaneous architecture created in perfect harmony with its natural surroundings was anything but a national shame. The Sassi were reevaluated, and in 1986 a law was passed to allow people to move back and once again breathe life into the stone districts.

Some Materani longed to return to the old neighborhoods and the camaraderie of village life played out in the Sassi’s small squares. Several case grotte (cave houses) have been renovated and function as cultural museums. Hotels, bed and breakfasts, bars and restaurants offer the experience of sleeping and eating in the Sassi. Ironically, many lodgings boast luxury cave accommodations.

MATERA – TOURIST DESTINATION

Historical and cultural offerings range from the splendid fresco paintings in the medieval chiese rupestri of the Sassi and its Murgia Materana Park to the area’s ancient artifacts and classic European art in the museums of the Piano district (“Domenico Ridola” National Archeological Museum and “Palazzo Lanfranchi” Medieval and Modern Art Museum).

“Snow Effect” by Giacomo Di Chirico, Lucanian artist, at “Palazzo Lanfranchi” Medieval and Modern Art Museum

Repurposed Sassi real estate has also resulted in several evocative museums, such as the interesting use of space for contemporary art in the Museo della Scultura contemporanea, the Rupestrian Complex of the Madonna delle Virtù and the Casa di Ortega, as well as the multimedia history presentation in Casa Noha. Matera’s dedication and commitment to the future influenced its selection as European Capital of Culture, just as its strong connection with the past brought about the city’s UNESCO acknowledgement.

Matera is both a testament to survival and a manifestation of human achievement. Visitors come from all over the world to admire the architecture and art, to enjoy traditional food, to learn about and to soak up the unique atmosphere. They wander up, down, through and around the maze of streets. By day, the sun bounces off the bright white walls, and voices fill the streets as they have for millennia. At night, the Sassi sparkle like a life-size nativity scene, not just at Christmastime, but every day of the year.

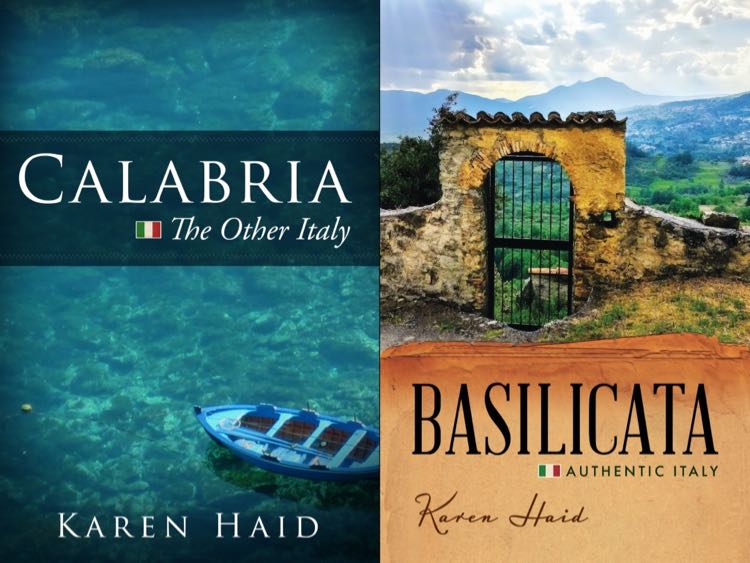

I originally wrote this article for the National Italian American Foundation and it appeared in the Summer 2019 edition of Ambassador magazine. Much more about Matera in my book Basilicata: Authentic Italy, described by the Library Journal as “an intimate exploration of an often overlooked region of Italy. Recommended to readers who appreciate all things Italian.”

Travel with me to the Southern Italian region of Basilicata and visit Matera on my BASILICATA CULTURAL TOUR!

Follow me on social media: Basilicata Facebook page, Calabria: The Other Italy’s Facebook page, Karen’s Instagram and Karen’s Twitter for beautiful pictures and information.

Sign up below to receive the next blog post directly to your email for free.

Comments 7

I love this. My mom and dad was born in Calabria gizzeria

Author

Glad you enjoyed my post. Windy Gizzeria!

Nicely written Karen! Matera is so hauntingly beautiful. I can’t wait to go back-but this time for more than a day trip. Ciao, Cristina

Author

Thanks, and yes, the Sassi are so bewitchingly atmospheric, an intricate structural maze with an equally complex history, worthy of a longer exploration.

I’ve long wanted to visit this part of Italy because of its architectural marriage to the landscape. Intriguing to learn from you how this town flourished, was abandoned, and ultimately managed to reinvent itself again.

Hope this finds you well.

Author

Yes, thanks. The organic nature of the architecture is truly amazing – hopefully, you’ll get to visit soon.

We have visited and explored the Sassi area twice. Once in 2008 and again in January 2024.

Philomena Talese