How many words do you know to describe the land? Language reveals a lot about a people. In Bova, Calabria, the Museo della Lingua Greco-Calabra “Gerhard Rohlfs” takes a closer look at this connection between the calabresi and their land, specifically the community that speaks an ancient Calabrian Greek language in the Aspromonte Mountains, way down south in the toe of Italy.

BOVESIA: GRECO-CALABRO– CALABRIAN GREEK IN BOVA, CALABRIA

Readers of my book Calabria: The Other Italy may remember my first visit to Bova, at the heart of the Bovesia, the last bastion of Greek speakers in the Province of Reggio Calabria. (The other Southern Italian enclave of historically Greek-language communities is the Grecìa Salentina near Lecce in the Salento peninsula on the heel of the boot.) In Calabria, the dialect spoken by an ever-dwindling handful of people is called grecanico or greco-calabro. The following map shows the areas where Calabrian Greek was spoken up until the ends of the 15th through 20th centuries before being supplanted by a Romance dialect, and then, in red, the locations where this ancient grecanico still survives, albeit with very few speakers. This Greek dialect is one of Italy’s official minority languages.

How long have they been speaking Greek in Calabria? Does this language stem from the time of Greater Greece, beginning in the 8th century BC or from the Byzantine Period from the 6th to 12th centuries AD? Scholars differ on this point. Although Calabrian Greek has followed its own developmental path, it is categorized as a modern Greek language with Calabrian and Italian influences. Interesting to note, however, that the grecanico in Calabria also contains numerous ancient-Greek words, which have long disappeared from the language spoken in Greece today.

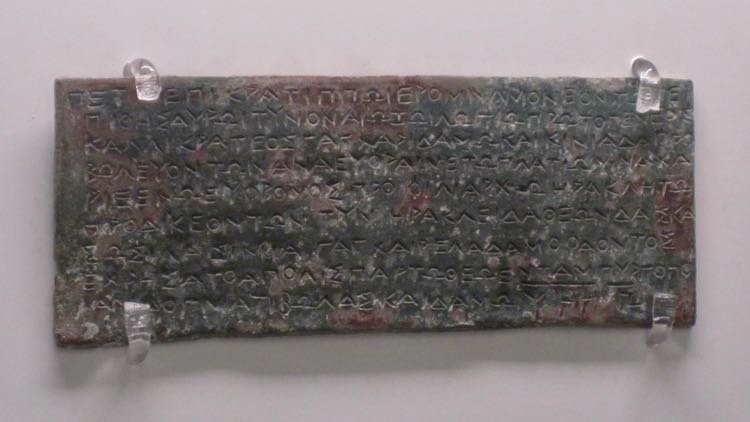

Bronze tablet in Ancient Greek, 4th-3rd century BC, from Locri Epizephyrii in Archeological Museum of Reggio Calabria

MUSEO DELLA LINGUA GRECO-CALABRA “GERHARD ROHLFS”

The Museum of the Calabrian Greek Language in Bova explores different aspects of the language through photos, historic documents and artifacts, as well as audio-visual material. Gerhard Rohlfs (1892 – 1986) was a German linguist, whose area of study was Romance languages, in particular, those spoken in Southern Italy. Often referred to as an “archeologist of words,” he asserted that Italian-Greek descended directly from the days of Magna Graecia, contending that the ancient Romans had not been able to Latinize the entire Italian peninsula.

Rohlfs’ many works include Griechen und Romanen in Unteritalien (Greeks and Romans in Southern Italy, 1924) and Dizionario dialettale della Calabria (Dialect Dictionary of Calabria, 1932), as well as many other scholarly studies and numerous documentary photographs. Rohlfs’ research is so respected in Calabria that he was given honorary citizenship by the towns of Bova, Candidoni, Tropea and Cosenza; there’s a piazza named for him in Badolato; and the Università della Calabria awarded him an honorary degree.

TA CHORÀFIA– THE LAND IN GRECANICO

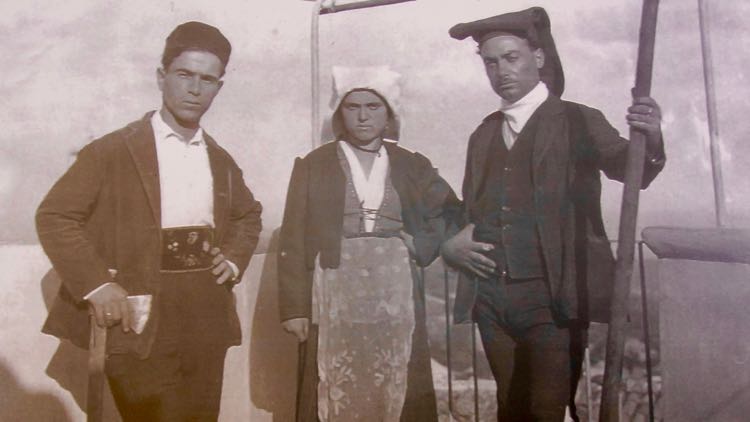

Apart from the numerous, beautiful photos of the local people, the exhibit that strikes me the most at the Museo della Lingua Greco-Calabra is a simple list of the many words from the grecanico language that describe the varietà e qualità dei terreni (variety and quality or characteristic of the land or terrain).

Rocky terrain, alone, has four words: ogliàra, ogliarùso, òlitho, rizzòlitho. Not to mention sterile and rocky terrain – sterèa; or hard, rocky and sterile terrain – traganò; or clayey terrain full of stones – lithràca. I would think that the upper part of a mountain slope – cefàloma, may be safer than the lower part – podàrìa, or maybe even better, a little plot of land at the bottom of a valley – laccàri. I’m clearly not a farmer; however, I think that all of the possible words for unstable, muddy ground would be important, ranging from slippery – zzìlistro, to terrain subject to landslides – calazàrìa. Mammamia!

I would like no part of poor, compact soil, difficult to cultivate – molisso. Just give me a little piece of humid, fertile soil with flakey clay – orgàda, preferably sunny land – andìglio, on which to set up my little vegetable garden – cipùri!

OLD TOWN OF BOVA, CALABRIA

The museum is located in what is often referred to as Bova Superiore, the old town located on the top of a hill, complete with numerous churches and castle ruins. Along the streets of historic Bova and down a hillside trail, the farmer’s life is also remembered in the Sentiero della Civiltà Contadina – Path of Rural Culture, with large millstones, olive and bergamot oil presses, drinking troughs, and other objects relating to the agrarian existence of the bovesi (people from Bova) not so long ago.

And for an unusual roadside attraction, a disproportionately large steam locomotive occupies a sizable space in a piazza, as many bovesi worked as ferrovieri or railroad workers. Construction of the railway along the Ionian coast began in 1865. Don’t worry, you can’t miss it – no need for Mr. Rohlfs’ dictionary!

Museums and even the attractions help keep memories of the old town and the old life alive. Many bovesi moved to the coastal town of Bova Marina and much further beyond. Today, Bova, Calabria counts fewer than 500 residents. Although it has its fair share of abandoned houses, many have been renovated to the point that the historic center has been named one of the Borghi più belli d’Italia (Italy’s most beautiful villages) as well as one of only eighteen in Italy to be named a Gioiello d’Italia (Jewel of Italy).

LANGUAGE FUTURE IN BOVA, CALABRIA?

Will grecanico survive? Very few young people speak their native tongue, and with the focus on English and other languages, Latin and even ancient Greece in the schools, the prospects are less than rosy. Several cultural groups and schools offer classes, but learning a modern language is difficult, no less an ancient one. To dedicate the proper amount of time and energy, there must be a very strong motivation.

The Bovesia has several groups that promote Calabrian Greek and the grecanico culture, such as GAL Area Grecanica, Circolo culturale Apodiafazzi, Associazione Jalo Tu Vua, and Circolo Paleaghenea. They offer language courses, cultural seminars, books and videos, as well as organize day-trips to the many historical and naturalistic sites of the area grecanica or Greek area. I first visited the Museo della Lingua Greco-Calabra with Ìmmasto, a local cultural organization that has taken the name “We are” in this ancient Greek language.

We have been and we are speaking Greek and bringing forward this unique culture into the 21st century.

The Museo della Lingua Greco-Calabra is located on Via Sant’Antonio in Bova, Calabria – check its website for up-to-date opening hours before your visit.

Visit Bova on my Calabria Cultural Tour – check out the full itinerary here: Calabria Tour.

More about the Bovesia in Calabria: The Other Italy and in my blogposts Palizzi: Yesterday and Today, Gallicianò: Greek Culture in Calabria, Pentedattilo: A Ghost Town in Calabria, The Castle of Amendolea and The Castle of Sant’Aniceto in Motta San Giovanni.

Check out my books “recommended to readers who appreciate all things Italian” by the Library Journal.

Follow me on social media: Basilicata Facebook page, Calabria: The Other Italy’s Facebook page, Karen’s Instagram and Karen’s Twitter for beautiful pictures and information.

Sign up below to receive the next blog post directly to your email for free.

Comments 10

ALWAYS learning SOMETHING from your articles!!! 😄

Author

Very happy to hear it!

I see someone’s doctoral dissertation here. Has one ever been done on the subject?

Author

A couple of years ago, I remember seeing information about a young woman of Calabrian descent working on her thesis with this topic at a British university. I imagine that the subject would also spark young Greek students, in particular, as well as the sons and daughters of families that immigrated from this area to all parts of the world.

By the way: it’s not Greek. Greek developed from our language. It is the one spoken by Plato Aristotle etc.

Great post Karen.

I hope that the language survives as too often, languages are lost over generations.

I’ve often wondered whether when Italians (or other nationalities) left their country, whether the language stayed the same in the new country, but the language evolved over time in their mother country. I noticed this with my father’s dialect living in Australia. When I visited his village in Calabria, the dialect was slightly different to what my father spoke – interesting.

Author

Thanks, it’s a fascinating topic. I would think that language has the tendency to change no matter if in the country of origin or in the new land; however, Calabrians have told me that the emigrants tend to speak what sounds to the locals, like a more dated form, which would make sense as they’re speaking the language of older generations.

Bova looks like such a charming place, I really hope I can get there and visit it! I also admire what they are doing to try and preserve the language.

Author

Absolutely, Bova is very interesting and definitely worth a visit!

Very interesting information.. my Italian grandparents, uncles & aunts said ‘we are bovanes’ when I asked. I never researched their & my ancestry.. grandparents lived with my family.. grew wonderful garden veggies & fruits, played opera on the Victrola and encouraged me towards a classical education where I studied latin & greek languages, history & philosophy.. not certain about a connection with Bova.. DeAngelo & Bavela were family names..